Lincolnshire’s First Detective by Jim Snee

One of the staples of daytime television is the detective series. These entertaining programmes are based around an individual (occasionally even a police officer) who uses clues to solve one of the many murders that take place in their particular locality. Sadly (or should that be thankfully), none of these series are set in Lincolnshire.

Which is a shame, because Lincolnshire’s landscape would provide an amazing backdrop to a detective series and, although people here are generally law-abiding, we have had our fair share or colourful crimes and gruesome murders.

Modern detective work is firmly in the hands of our Constabulary and has been since it was formed by the 1856 County and Borough Police Act.

The popular idea of the detective as someone other than the police solving crimes comes from the fiction of the late 19th Century, most famously the stories of Sherlock Holmes. In many ways this fiction is an indication of the transition that was taking place between law enforcement by the traditionally appointed individuals such as Justices of the Peace and parish constables and the modern state police force.

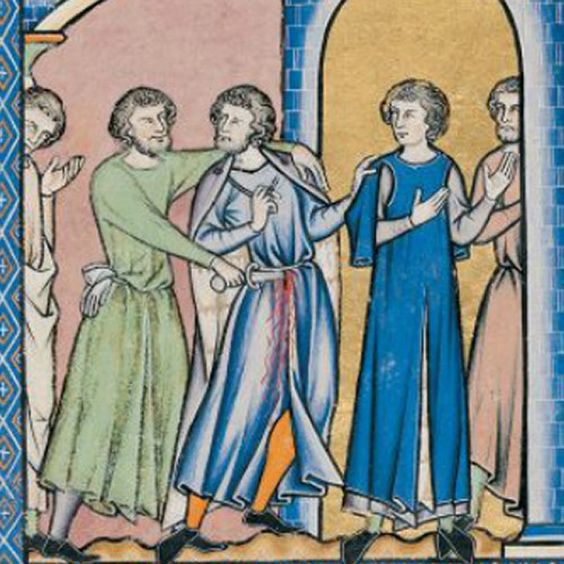

In Lincolnshire the system of justice was established in the medieval period and continued through the centuries that followed with few structural changes. That is not to say that the law didn’t evolve and become more refined. In the medieval period the onus was very much on the accused to prove his or her innocence before the county sheriff, and that could mean a long spell in prison before your name was cleared. There is an example from Hackthorn where a man killed another in self-defence. The defendant spent a year in gaol in Lincoln Castle before he was acquitted on the grounds that he could not flee his attacker (his back was to the wall of the manorial dovecote). In other cases, there was an enduring sense of self-help, in that it was up to those who were wronged to bring evidence to support their claim. Parish constables were more concerned with keeping the peace and keeping order.

Naturally, this brought into play a number of individuals who sought to gain from what was, from the modern perspective, a lax state of affairs. Thief-takers, Witch-hunters and witnesses for hire were readily available, for a fee, to help right a wrong in the eyes of the law. Just as varied were the methods of finding wrong doers, including crystals, amulets and spells that revealed the miscreant’s identity. A far cry to what we consider detective work.

But the law did not magically appear in the medieval period, and there must have been some mechanism for seeking redress if not actual justice. For the Vikings, legal justice was a very democratic process that was enacted through the “Thing”, an assembly of the people where each side of the case was heard by all. It is worth noting that a detective in this era would not only have to gather witnesses but would also have to have some skill in oratory and poetry. In the saga of Egill Skallagrimsson there are several occasions where Egill’s natural ability to compose epic verse (he composed his first poem at 3 years old) succeeded in getting him out of the trouble that also came naturally to him (he killed his first man at age 6). There were also occasions where the judicial processes were overtaken by individuals taking the law into their own hands. On one occasion, during a raid, Egill and his follows are captured and the lord who captured them sentences them all to death by beheading. However, suspending the sentence to the following morning allows Egill to break free, rob the hall and execute most of the household, claiming his own rough justice. On another occasion, Egill did go to the Thing to seek justice, but his ability as an orator was such that the queen sent soldiers to prevent him from speaking. An act that lead to a long and bitter feud.

Prior to Lincolnshire being part of Danelaw, Saxon law was upheld by the King’s Sokemen. These were officers of the king who would act as circuit judges through divisions of the county called Sokes. Saxon society seems to be less democratic and more despotic than Viking society and a detective’s ability would have more to do with their social rank than the facts that they could accrue.

The Romans had a highly developed legal system. It was also constantly being decried for being corrupt and incompetent. If a Viking detective had to be a skilled orator, then the Roman detective had to be actor and conman combined. There are allegations of witnesses appearing in several trials disguised as different people, and lawyers wearing eye patches and false hunchbacks to gain sympathy.

We are told by Julius Caesar that Gallic and British law was handled by the nobility and the druids, but that the legal system did protect the weak, punish wrong doers and compensate the wronged. It appears that seeking justice would fall upon a faction leader within the household, clan or tribe. Thus, the detectives of Iron Age Briton would also be its warriors, chiefs and kings. This is certainly consistent with the early mythology of the British Isles.

Beyond the Iron Age we have no written evidence to look to, but that does not mean that there were no laws or justice. Considerable study has been put into origins and establishment of law, and it is found in all human societies. The first hunter gathers of the Palaeolithic had laws, and a means of enforcing them, should they be broken. It is believed that in these earliest societies it was very much a case of the wronged bringing the wrong doer to account, but that can be found in our more recent history as well.

So, it appears that when the first human in Lincolnshire was wronged and set out to right that wrong, they became a prehistoric detective. The first detective in Lincolnshire.