Lincolnshire’s First Footballer by Jim Snee

Lincolnshire has a long history of association football. Brigg Town FC, known as the zebras, is one of the oldest surviving clubs in the country, having been formed within a year of the encoding of the Rules of Association Football, in 1864.

Lincolnshire has a long history of association football. Brigg Town FC, known as the zebras, is one of the oldest surviving clubs in the country, having been formed within a year of the encoding of the Rules of Association Football, in 1864.

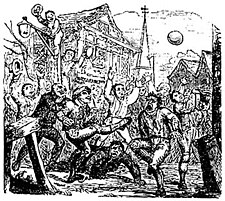

Prior to the more civilised game, Lincolnshire had a strong tradition of “medieval football” sometimes, and to my mind more accurately, called mob football. This was a raucous game that involved throwing a ball in the air between two teams of villagers and watching the ensuing fracas. If you want a taste of this activity, the Haxey Hood game continues the tradition to this very day. I suspect the game has continued in other parts of the county in a less celebrated manner. I know from my own experience that mob football was part of the curriculum of Gainsborough secondary schools until the late 20th century, where it was known as Mosh Ball. Although I must confess, I write this from the dubious perspective of being the first person sent off during a match since World War II.

In the 17th century we have a unique variation of mob football recounted as Fen football. This was a particularly rough form of the game played by those protesting against the drainage of the fens and the enclosing of former common lands. As with other forms of medieval football, the ball was tossed into the air and the two teams would chase it. However, there was a stipulated tradition that the ball must remain “free” and its progressed should not be impeded by walls or fences. So as the match progressed, whenever the ball came to rest against an artificial obstruction, be it fence, barn or house, both teams would unite to demolish the obstruction before returning to their former conflict.

Traditional football games are well recorded around the world and are even known in ancient Roma, but so far, no hard archaeological evidence (carved images, tomb paintings etc…) of pre-medieval football has come to light.

So, to find our earliest footballer, we must look to a medieval story and, sadly, one of the darker episodes on Lincolnshire’s history.

On the 31st July 1255, 9-year-old Hugh of Lincoln (or so it is said) was playing football with other youths somewhere close to the Castle. It is said that he kicked the ball over the wall of Jewish property, went to recover it and disappeared. On the 29th of August, his body was discovered in a well. The Bishop of Lincoln and his brother accused the Jewish community of Lincoln of “Ritual Murder”, a crime commonly used to justify anti-Semitic persecution. A confession was obtained under torture and, with King Henry III present to lend royal force, a number of Jews were imprisoned and executed, with many more driven out of the city.

The murdered boy was unofficially canonised, dubbed Little St Hugh. His body was transferred to Lincoln Cathedral where a magnificent shrine was built. It is said that healing miracles took place at the shrine, but if the Bishop of Lincoln had believed he had founded an enduring cult, he was mistaken. Pilgrimage to the shrine lost popularity over the coming decades and during the reformation of the church the shrine was defaced. Curiously, the tradition of Little St Hugh the footballer survived longer than his status as a Christian martyr, with folklore and song surviving across the British Isles and beyond, to America where people from this country settled and established English traditions.

Perhaps it is best to remember him as Lincolnshire’s 1st footballer. Certainly, the Church of England do not want a resurrection of the old cult of child martyrs. In 1955, a plaque was placed at the site of the former shrine. It reads:

By the remains of the shrine of “Little St Hugh”.

Trumped up stories of “ritual murders” of Christian boys by Jewish communities were common throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and even much later. These fictions cost many innocent Jews their lives. Lincoln had its own legend and the alleged victim was buried in the Cathedral in the year 1255.

Such stories do not redound to the credit of Christendom, and so we pray:

Lord, forgive what we have been,

amend what we are,

and direct what we shall be.