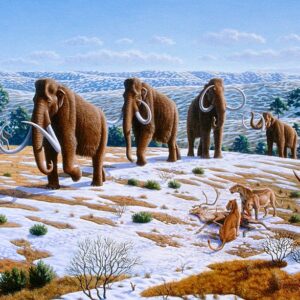

There aren’t many Mammoths roaming around Lincolnshire these days. Other forms of glacial megafauna are pretty thin on the ground as well. So as archaeologists, we have to ask the question why?

There aren’t many Mammoths roaming around Lincolnshire these days. Other forms of glacial megafauna are pretty thin on the ground as well. So as archaeologists, we have to ask the question why?

That megafauna once did roam Lincolnshire is proven by occasional finds of bones and teeth, and occasionally skeletons such as the Mammoth and Woolly Rhinoceros remains at Pode Hole Quarry in the fens.

So what happened to them. The short answer is they became extinct around the 11th millennium BC and that their extinction marks the beginning of the sixth extinction event, also called the Holocene extinction. That extinction event is still going on.

So why did large numbers of species start becoming extinct in the last twelve thousand years? The popular answer is that humans are responsible. The problem with popular answers is that they are often gross oversimplifications.

The evidence for human-caused extinction is based on the coincidence in timing, and the recent history of human-caused extinction events.

As the ice sheets retreated, humans recolonised areas of the planet that had been abandoned tens of thousands of years previously. The theory goes that human hunting, coupled with predation from human tolerant animals like wolves (early dogs) brought the species of megafauna to their end, and that continued human development such as the invention of farming continued the process.

There are some caveats, however. Humans have been around for approximately 4.5 million years and have previously colonised the areas where megafauna lived, without causing a mass extinction. There is also the fact that we were not the only colonising species on the planet. In my last article, I explained the huge environmental change brought about by the colonisation of the land by trees.

There is also the driving force behind colonisation by humans (and trees), which is climate change. It is estimated that average global temperatures underwent a 6 degree rise during the first two millennia of the Holocene. Compare that to the 1 degree increase in the last 2000 years and you can see how dramatic a change that would be. Species adapted to the cold would have been forced to follow the retreating ice sheets, occupying smaller and smaller territories that would not have been able to sustain strong populations of large herbivores. Add humans to that, and you have a disaster waiting to happen.

Other events also take their toll, climate and disease caused the dominant plant species to change, and the routes of migration were also forced to change. In the middle of the Mesolithic, the land bridge between Britain and Europe (Known as Doggerland) was flooded, possibly by a single great deluge. Lincolnshire was, for the first time since the advance of the glaciers, on the coast again.

It’s hard to migrate to your seasonal feeding grounds when there’s suddenly an ocean in the way.

Humans, like all the other species of fauna and flora, responded to the change in climate. They moved north, they changed their hunting practices and they prospered. In doing so they added to the pressure on animals already under immense stress.

It was a vicious circle in which our early ancestors were caught, but they were not the driving force. That was climate change.

But the actions of humans would also affect climate change, and the story goes on…

During the Mesolithic, traditionally hunted species of megafauna moved away or died out (or both). Migrations that had taken place for millennia stopped and Britain became an island. The human population was forced to change the way it lived and hunted. New species were added to the diet, becoming more important over time, and new smaller prey animals required a change in hunting tactics. The strength of arm and numbers needed to kill a mammoth were of little use when hunting red deer. More change was coming to the people of Lincolnshire.