Monument

Lincoln Castle

Lincoln Castle was built almost 1,000 years ago by William the Conqueror. After his victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror faced ongoing resistance and ordered the construction of a Castle in Lincoln as part of his strategy supress rebellious activity in the North of the Kingdom. The castle’s strategic location on top of the hill acted as a reminder to the local population that the Normans were in control.

The Normans constructed their motte and bailey castle by re-using the remains of stone walls that were part of the Roman city, Lindum Colonia. We also know that centuries earlier, Roman invaders built their legionary fortress on the same hilltop. The castle walls were built in stone in the late 11th century, replace a temporary wooden palisade.

Lincoln Castle Revealed

From 2010 – 2015 Lincoln Castle underwent a major £22m restoration project funded by various bodies including the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The project undertook a variety of works but a large proportion of the restoration works took place on the Castle’s curtain wall resulting in a creation of a new 360-degree Medieval Wall Walk along the Castle’s ancient ramparts.

Skills used at Lincoln Castle

Roof

Good restoration and building work will last for years with appropriate maintenance.

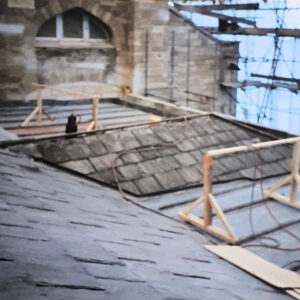

The roof of the prison building was stripped, repaired and re slated in the early nineties. As it remained in good repair it wasn’t looked at as part of the 2010-2015 restoration and conservation works.

The Lincolnshire vernacular roofing material is pan tile and can be found on many historic buildings around the county. As a prominent public building however the Prison roof was covered in slate. Not only was this a display of status, slates depending on how they are laid would also be more air and weather tight.

Traditionally Slaters would have their own measures of slate that they were using. This would be kept on a marking stick which would then be unique to each slater. By marking and sizing the slates to their own measures no one else was able to steal and reuse their materials.

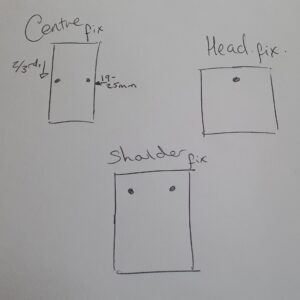

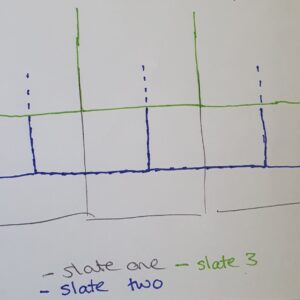

Slates can be attached to a roof in a variety of ways:

Perhaps the most common is the centre fix, it generally dates from industrialisation. A centre fixing involves to pegs/nails being used on either side of the slate, about two thirds of the way down from the top and somewhere between 19-25mm in from the edge.

If you look at the prison roof now what you will see is random diminishing (this means it gets smaller as it goes up towards the roof ridge from the wall) county grade slate. Where possible slates that had been removed from the roof were reused meaning that as much original material was kept as possible. Welsh slate from Penrhyn quarry, Bethesda North Wales was used to make up the short fall replacing slates which had broken or were no longer good to go back on the roof.

The slates were attached with a centre fix involving two copper nails to the rafters they range in size from 48 inches at the bottom to 20 inches at the top. They also have some lime mortar applied to help bed them in place too, but you can only see this from inside the roof space.

Stonework conservation

A large part of resent restoration works at Lincoln Castle involved the Castle's stone curtain wall. The use of minimal intervention as a conservation principle allowed for high proportions of the existing wall fabric to be retained. Keeping in mind conservation principles some key actions during the works are highlighted below.

- Sections of the walls were overgrown with vegetation some of which were rooted within the wall fabric, adding excess moisture to the stonework, damaging it. Careful excavation was essential to remove the vegetation and hopefully conserve as much of the original fabric as possible.

- Repairing stone rather than replacing where possible. During the first phase of the works the team were able to retain a significant portion of the original fabric using approximately 260 tonnes of new stone.

- Hiring experienced local craftspeople with specialist stone conservation knowledge, including knowledge of local geology and local building/construction methods meant that care had been taken to find people who would be able to do the repairs to the existing stone fabric as well as integrate new stones where needed.

- The new stone fabric was sourced from the local Lincoln Cathedral Quarry and then hand prepared for the castle walls by 23 stonemasons. It took them approximately 2 hours to prepare each stone before it is set in place on the walls.

- Creating a lime mortar to match and integrate the new fabric with the old was an important part of the works. Achieving the right mortar mix in terms of texture, appearance, colour and consistency means that the repairs would blend into the original fabric. 8 test frames of different mortar mixes were created by the team before approval. In the end sand from Norton Disney, 11 miles from site was used to create a more accurate match, so that when the new stones weather and blend in with the original ones the restoration work should appear to be minimally invasive.

Lime mortar

Mortar is a workable paste which hardens, and it binds building blocks including stones, bricks and masonry units, allowing to fill and seal irregular gaps between them. It has been made in the same way for over 1000 years, it first appeared in Britain during the 4th century. The word ‘mortar’ is derived from the old French word mortier which means builder’s mortar, plaster or bowl for mixing.

The mortar was traditionally made of slaked lime, sand and an additive or binder. Many kilns were used to create limestone along the coast of Britain.

Process of creating lime mortar:

- Firstly, the limestone would be smashed into small chunks allowing it to be heated when it was added to the kiln. The base of the kiln would be filled with coal, and then filled using layered coal and the small broken pieces of limestone.

- After the kiln was layered adequately, a fire would be started at the base of the kiln. The burning process could last for up to 2 days depending on how big the kiln was. The coal would reduce in size, more coal was added allowing a longer burning process rather than doing individual burns which would be more time consuming.

- Eventually the coal would turn into ash and fall out of the bottom of the kiln, along with the pieces of limestone. A rake tool would then be used to pull out the hot chunks of limestone as they fell out of the bottom of the kiln.

- If the limestone was cooled naturally it created quicklime, if water was added to the hot pieces of lime it turned in slaked lime. Using water to cool the hot pieces of lime whilst they were still hot enabled it to become more brittle making it easier to smash it into powder.

- The powdered slaked lime would then be used on construction sites where an equal amount of sand would be mixed with the slaked lime powder then water was added to create the right consistency. Many castles and homes were built using this method.

Designation

Designation aims to highlight the significance of a heritage asset and to help make sure that any future change to that asset does not result in the loss of its significance.

Heritage Assets of all type can be designated and the terminology for each asset type is different and carries different weight in legislation. Some designations are straightforward, and others are slightly more complex with different levels of grading.

Listing is a national designation covering buildings. A listing is a record of the special architectural, or historic interest of that building.

There are estimated to be over 500,000 Listed Buildings on the NHLE.

Listed Buildings are graded in line with their level of special architectural, or historic interest. The decision to include a building on the NHLE rests with the Secretary of State for Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS), the Secretary of State is advised in this process by Historic England and their Listings Teams based around the country.

- Grade I Buildings are of exceptional interest with only 2.5% of all Listed Buildings in this category.

- Grade II* Buildings are particularly important buildings of more than special interest, only 5.8% of all Listed Buildings fall in this category.

- Grade II Buildings are of special interest and is the most common grading with 91.7% of all Listed Buildings covered by this grading.

The requirement for Listing buildings currently comes from the Planning (Listed Buildings & Conservation Areas) Act 1990 – Section 1 & 2.

The Listing of a building affords it statutory protection meaning that in most cases, works to that building that affect the special architectural, or historic interest will require Listed Building Consent. In some instances, Planning Permission may also be needed. It is best to check with your Local Planning Authority which consents will be required when looking to make changes to a Listed Building.

Undertaking unauthorised works to a Listed Building is a criminal offence.

Designation is not a top-down process, and anybody is able to nominate a site for designation to Historic England.

Nationally designated heritage assets have been recorded and available to view online via the National Heritage List for England: