Churches

What survives today

Topic 1: Churches

The most common and obvious medieval building found in villages, towns and cities is the church.

This was an important community building and often occupied a prominent position in the settlement.

However, many of Lincolnshire’s churches have been altered or even rebuilt over the centuries, so it is worth taking a close look to confirm the medieval origin of the church in question.

All Saints church at Heapham (Photo: Heritage Lincolnshire)

Research

When looking at churches for clues to their medieval past, it is worth fore-arming yourself with some information.

A good source for this is The Buildings of England by Nikolaus Pevsner, which has a volume devoted to Lincolnshire. This will provide a description of the architecture of the church, with some information about the date and any interesting monuments etc…

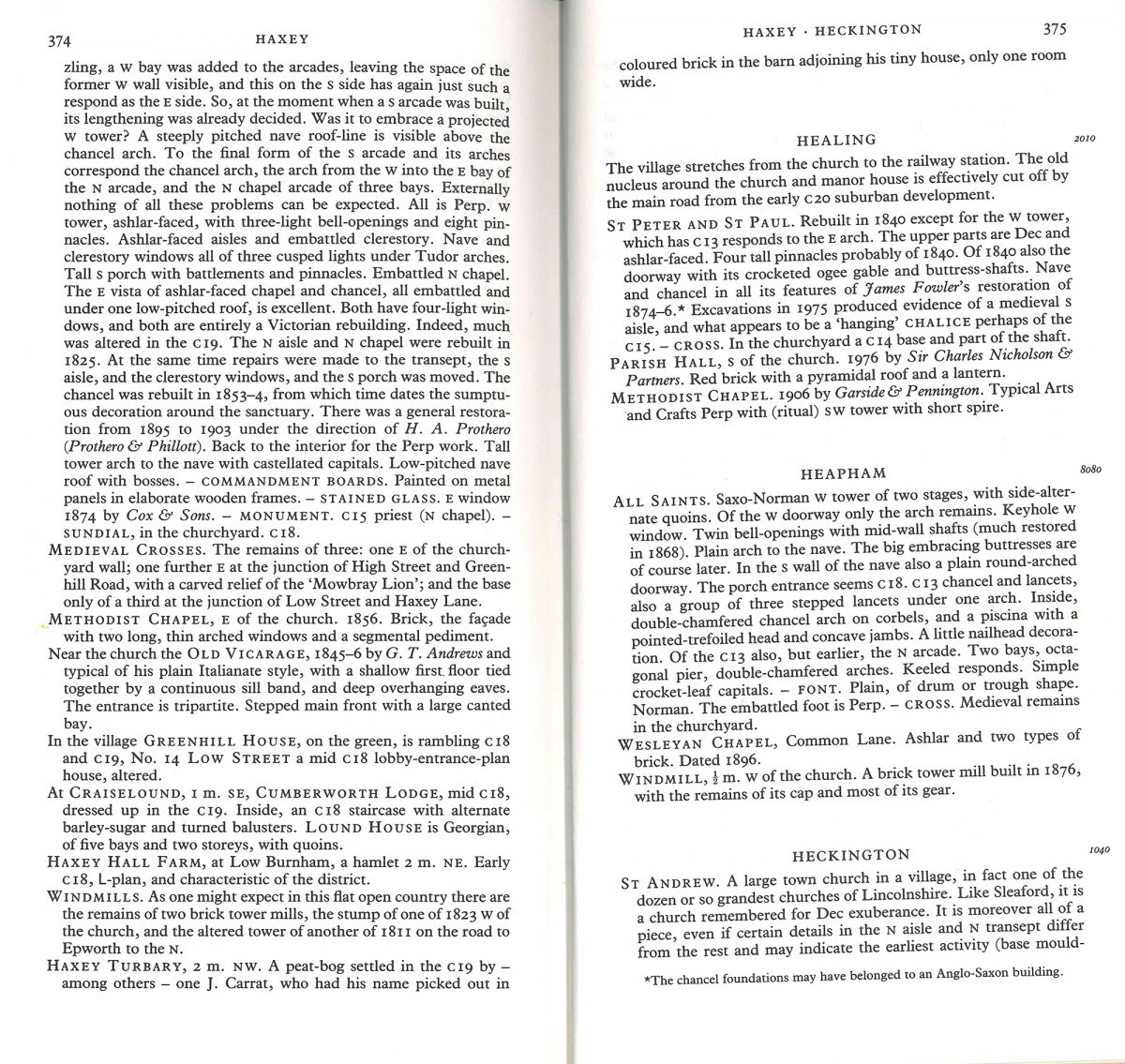

Page from Buildings of England: Lincolnshire by Nikolaus Pevsner

For example, the description of Heapham church reads:

ALL SAINTS. Saxon-Norman W tower of two stages, with side-alternate quoins. Of the W doorway only the arch remains. Keyhole W window. Twin bell-openings with mid-wall (much restored in 1868 by James Fowler). Plain arch to the nave. The big embracing buttresses are of course later. In the S wall of the nave also a plain round-arched doorway. The porch entrance seems C18. C13 chancel and lancets, also a group of three stepped lancets under one arch. Inside, double chamfered chancel arch on corbels, and a piscine with a pointed-trefoiled head and concave jambs. A little nailhead decoration. Of C13 also, but earlier, the N arcade. Two bays, octagonal pier, double-chamfered arches. Keeled responds. Simple crocket-leaf capitals. – FONT. Plain, or drum or trough shape. Norman. The embattled foot is Perp. – CROSS. Medieval remains in the churchyard.

Decoding the text

At first glance this will appear to have been written in code, and in a way it is. It is a set of notes for architects, and as such uses common architectural terms, some of which have been abbreviated. Fortunately the Buildings of England books contain a glossary, and with this we can decode the text.

The notes begin with the name of the church, ALL SAINTS, which tells us that this is All Saints church, Heapham. It then begins its description of the exterior of the west (W) tower which is assigned a date of Saxon-Norman, which covers the period between 1060 AD and 1100 AD, and says that it was having two vertical stages and large corner stones laid in alternate directions.

The tower of Heapham church, you can see the buttresses, the blocked door at the base, the small window halfway, and the openings for bells at the top.

It notes the arch that is all that remains from a blocked up west door, a small (Keyhole) window on the west side of the tower, and the openings at the top of the tower where the bells are held and were restored in the mid 19th century. The next sentence describes the archway from the tower to the nave (main room of the church) as it is seen from inside the tower. Finally the text comments on the two corner buttresses that encase the corners of the tower and are in fact a later addition to the structure.

Arch between nave and tower (Photo: John Tucker)

The next part of the text describes the nave of the church and begins with the round topped arch between the nave and the tower, as seen from the nave. A round topped arch of this type is likely to be an early feature.

The exterior of the nave, showing porch and windows.

The text then describes the exterior of the nave, noting the addition of an 18th century porch, 13th century lancet (slender pointed) windows and the 13th century chancel, which also has lancet windows. One of the windows is a group of three lancet windows, with the middle window slightly higher, under a single arch.

The description of the interior of the church begins with description of the arch that goes from the knave to the chancel. It is described as double chamfered, which means that the inside edge of the arch is stepped and each step has the sharp edge removed (chamfered). The shaped stones that form the arch are supported from stones that project from walls, these are called corbels. The piscine mentioned next, is an alcove in the wall that held a shallow bowl used for washing the communion vessels. These are often near the alter in a church, in this case in the chancel itself. The alcove has three pointed arches at the top, and the jambs are the moulded supports for the arches at the sides of the opening.

Exterior of the north isle.

The next description is of the isle that has been added to the north of the nave. It has two arches supporting the remains of the former north wall, referred to as bays. These are each composed of an arch supported by an eight-sided pillar and a half pillar set into the wall (the keeled respond) with decorated tops, and are doubled chamfered in a similar manner to the chancel arch. It is noted that the north isle is of a similar date to the chancel, although possibly slightly earlier.

The font is dated to the Norman period and is an undecorated cylinder with a basin formed at the top. The foot is a later medieval (perpendicular gothic) addition and has embattled moulding, that is it has indentations like those of a battlement.

Remains of a medieval cross.

Finally, the text notes that the remains of a medieval cross (in this case the shaft) can be found in the churchyard.

Now this is a lot of architectural information, but also some useful clues for the landscape archaeologist.

The identification of the nave and tower as part of a Norman, possibly even Saxon church is significant as this means that the settlement was an established village by the time of the Norman conquest in 1066.

The expansion and modification of the church in the 13th Century also suggests that the settlement was flourishing during that period.

We also have a later medieval modification of the older font. This suggests that while the church may not be expanding, it is still receiving patronage of some kind. Evidence of this patronage is also found in the form of the 18th century porch.

Interestingly, while the 19th century saw significant rebuilding of churches throughout the county (and indeed the country), this church appears to have had less renovation, possibly restricted to the tower.

From this we could speculate that while the church is still in use, it has neither a large congregation or wealthy patron looking to modernise or enlarge the church.

So, the architecture of the church actually suggests a story of established settlement, growth, stagnation and possibly even decline.

Examination of other churches and structures will reveal their own stories.