Medieval Dwellings

Lost and Shrunken Villages

Topic 3: Medieval Dwellings

Long Houses

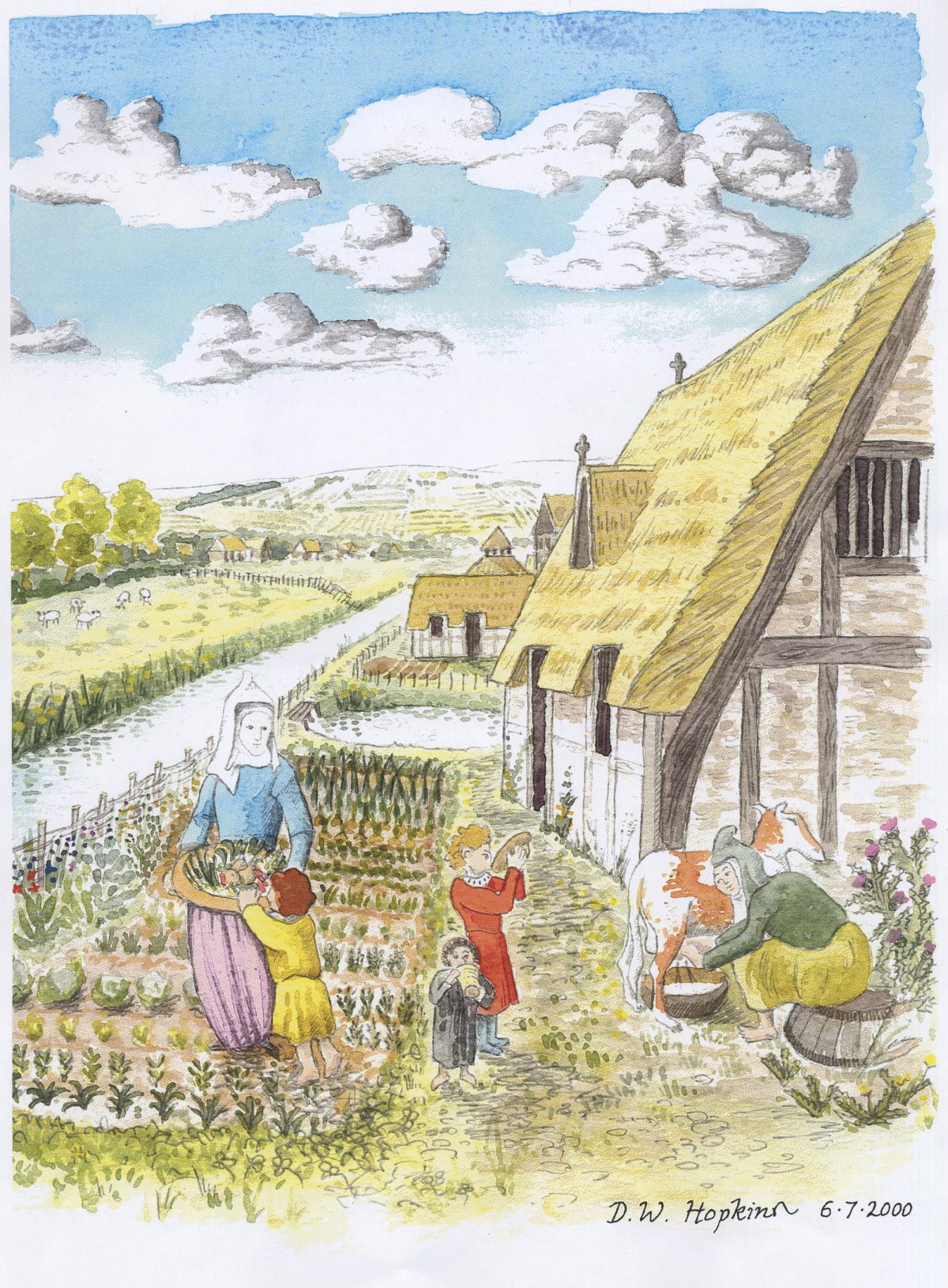

The principle form of medieval dwelling in rural Lincolnshire was the hall house, often referred to as the long house.

This was a single structure that provided accommodation for both people and livestock.

The construction and form of these medieval houses was fairly standard across the country and would have comprised of a simple timber frame with mud walls and a thatched roof.

The interior would have been open to the rafters. Additional features were a fireplace, where the people dwelt, and a drain for the livestock.

Doorways would have been located opposite each other, close to the middle of the long sides of the building, and windows would have been small, possibly even slits.

Reconstruction of a medieval house and garden by David Hopkins.

Tofts and crofts

Following the abandonment of villages, or parts of villages, the houses were left to decay and collapse. As a result, there may be a rectangular or L-shaped mound or bank (sometimes called a toft) that indicates the presence of the house.

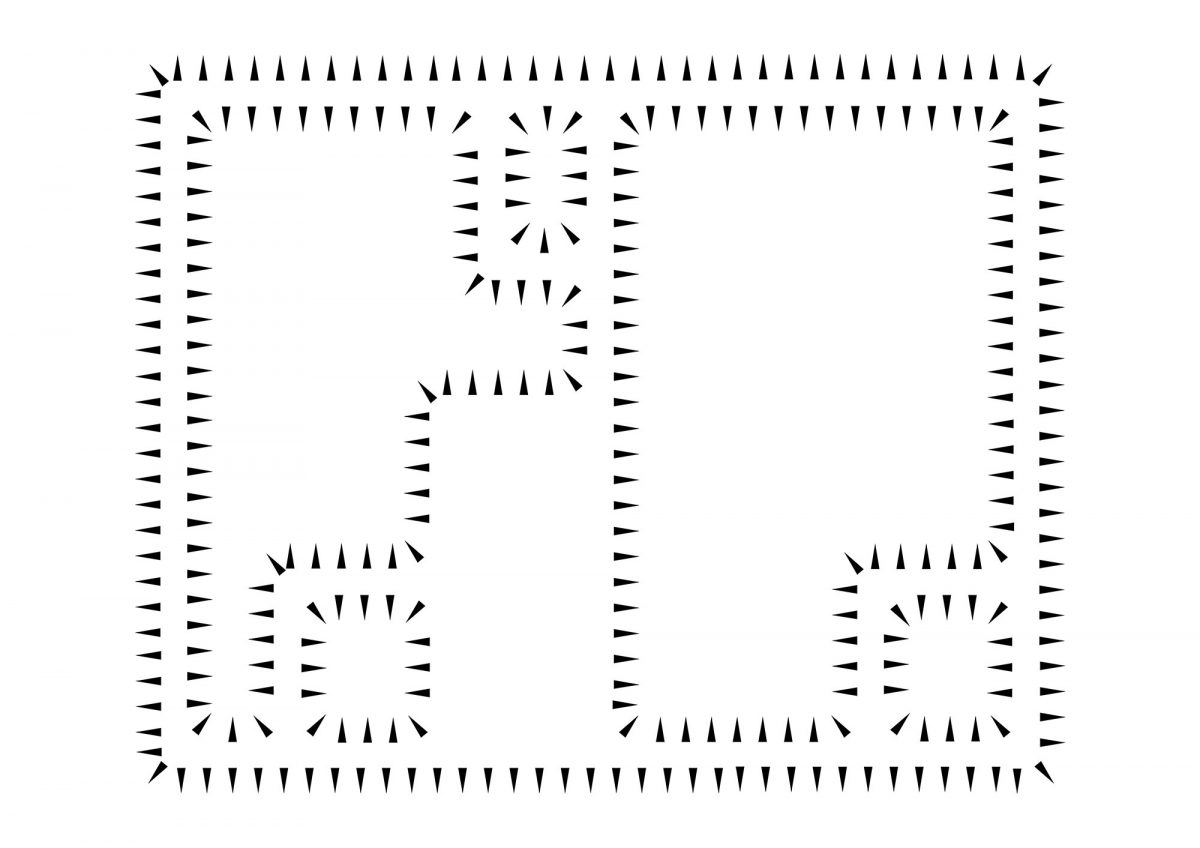

Schematic tofts and crofts, based on Hackthorn earthworks, with a simple dwelling on the right and a more complex and wealthier dwelling on the left.

The size and complexity of the surviving earthwork is a fair indication of the size and complexity of the original building, and therefore the relative prosperity of the family living there.

A small single cell toft would indicate a poorer family

A larger toft divided into several rooms or cells would indicate a more prosperous family.

As the medieval period progressed, the hall became to develop and become more refined. Partitions were added to separate livestock from people, mezzanine floors added additional sleeping space, and central fires were replaced with inglenook fireplaces with smoke hoods.

These houses were often set in a garden plot, known as a croft. This might also contain ancillary structures such as additional stalls for animals, granaries or workshops. These are sometimes visible as rectangular banks or other bumps in the ground.

Fields

A single farmstead would be surrounded by fields, some of which may be enclosed (called closes), but more often open. Enclosed fields and crofts would have bank, ditch or hedge boundaries, which can remain in place even to the present day.

Roads

Medieval roads and lanes can often be preserved between field boundaries, they may also be preserved as linear hollows known as hollow ways. It is worth noting that many medieval roads and lanes are very narrow by modern standards as they were most commonly used for pedestrian traffic.

Groups of houses would be formed into hamlets villages or townships. The houses, garden plots and ancillary buildings would have been essentially the same as those of a farmstead and were often enclosed with a bank and hedge. In Lincolnshire, it was common for the house to be adjacent to the road, and perpendicular to it.

So, you can see that even when a village has almost completely disappeared, you can still build up a picture of the layout of the village and the size of houses within it. Instead of an empty field of humps and bumps, you can picture a living, bustling village.